The American literary scene has many robust literary traditions-African American Literature, Asian American writing, Jewish writing, immigrant writing-that illuminate the experience of being a minority, of being from elsewhere, and of reinventing home. Svetlana Boym, the Harvard scholar and Russian émigré who passed away last month, too young, wrote eloquently about how migration inspires the invention of new forms of homeliness in one’s new country, often marked by an affectionate farewell nod to the homeland left behind: she calls this exilic or “diasporic intimacy.” The Jewish Indian writer Esther David’s part novel part memoir Book of Esther speaks to both, the invention of diasporic intimacy, and American traditions of migrant and minority literatures.

Indian and Indian American fiction writers who address ethnic diversity and minority experience often dwell on regional as well as Hindu-Muslim differences (Salman Rushdie, Vikram Chandra, Jhumpa Lahiri, Shauna Singh Baldwin, Bharati Mukherjee,and others), and caste discrimination (Arundhati Roy, Aravind Adiga, Manil Suri). In this arena, Canada-based Rohinton Mistry’s fiction revolving around Parsis or Zoroastrians, who migrated from Persia to India in the 8th to 10thcentury, offers a beautiful glimpse of a minority community that has made remarkable contributions to modern India. Similarly, born into the Bene Israel community in India, Esther David vividly illuminates life in India’s small, ancient, and remarkable Jewish community. The Bene Israel are considered by some to belong to the Lost Tribes of Israel. Accounts of their arrival vary: H. S. Kehimkar suggested that their ancestors washed ashore from a shipwreck off the Konkan coast, in Navgaon, when they were persecuted in the Galilee by Antiochus Epiphanes (173-163 B.C.E.). Others, like D. J. Samson, argue that the Bene Israel arrived in India between 740 and 500 B.C.E. Originally a farming and oil-pressing people, they held on to some Jewish customs and practices, while adopting Konkani dress, food, and the Marathi language. Under British rule, they prospered and migrated to urban areas, where the establishment of synagogues, education, and travel revived their Jewish traditions. As the Jewish genealogical journal Avotaynu notes, “The Bene Israel flourished for 2,400 years in a tolerant land [India] that has never known anti-Semitism, and were successful in all aspects of the socio-economic and cultural life of the people of the region.”However, emigration to the Americas, Europe, and Israel since1947-48 has left barely 4000 Bene Israel members in India today.

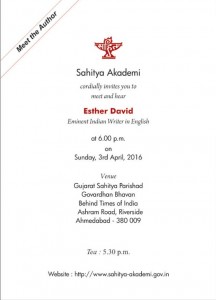

Esther David (b. 1945) grew up in the western city of Ahmedabad, spending much of her childhood in and near the Kamala Nehru Zoological Garden established in 1951by her veterinarian father Reuben David. Later, Reuben also founded the Natural History Museum in Ahmedabad. Trained as an artist, Esther David first wrote art criticism for leading newspapers like Times of India, before turning to fiction. Unlike the award-winning work of India’s other Bene Israel writer, the late poet Nissim Ezekiel, Esther David’s large corpus of fiction revolves around the Bene Israel, and especially, women’s experience. Her novels and short stories are published in the US and India, and translated in multiple languages. They straddle India, Israel, France, and the US, and have garnered recognition in India and abroad. For example, the Hadassah-Brandeis University 2010-2011 calendar featured David’s novel Shalom India Housing Society as one of 12 international Jewish women’s works. In 2010, David won India’s highest literary honor-the Sahitya Akademi Award.

Book of Esther is an autobiographical novel; its multi-generational story of the Dandekar family is rooted in family tales, photographs, diaries, letters, and memories. It begins in the nineteenth century with the story of a female protagonist Bathsheba who lives in a small village Danda, while her husband is off fighting wars as a soldier in the British army. In four sections, each named for a central character in a generation-“Bathsheba,” “David,” “Joshua,” and “Esther”- the novel traces the lives and loves, marriages, migrations, and family conflicts of four generations. The story of these many intimacies is tied up with how its characters navigate the vicissitudes of British colonial occupation, find work in the East India Company and the British army, win local elections, or become doctors; how they transmit, preserve, and perform Jewish traditions and identity in everyday life; how they throw in their lot with the Indian freedom struggle, plan to emigrate to Israel and America, or reinvent tradition and belonging in independent India.

The characters of Book of Esther are drawn in bold brush strokes that make them endearing and memorable: for instance, Bathsheba embraces an unconventional gender role, when, as a woman living in a hamlet, she expertly starts running the family farm because her soldier-husband is away. From Bathsheba and Solomon’s marriage, to her conflicts with her daughter Tamara, and the failures of romance and marriage in the lives of Tamara and later, Esther, we see strong Jewish women who negotiate complex diasporic intimacies—fragile, emergent, and at times, dispossessing. The narrative is littered with details that lend texture and color to these stories about minority intimacies. When David describes Jewish traditions performed in the rituals of birth, marriage, food, death, and festivals by the various characters, the intermingling of local languages and practices with Jewish custom illuminates the startling hybridity of Jewish Indian everyday life. This is a rarely visible India on the global stage—one that David wonderfully opens up for us. For instance, one day, Bathsheba and Solomon make a pilgrimage to a stunning rocky clearing in a small hamlet Sagav where it is said Prophet Elijah had appeared: “They washed their feet in the clear water of the pond and walked around Eliyahu Hannabi cha tapa as one did in a temple. Abigayail had whispered to Bathsheba that Eliyahu Hannabi was their Ganesha. All auspicious occasions started with the Eliyahu Hannabi, the same way that the Hindus started everything with the Ganesh sthapan. In the land of idols, the relic was an image which helped the Bene Israel relate to their prophet.” (43)

This moment of cross-cultural translation is not an urbane and elite cosmopolitanism; it unveils instead a vernacular intermingling of cultures as a practice of survival, on the one hand, and of exuberant invention and bricolage in rural and provincial spaces, on the other. This is an intensely provincial hybridity; it links with how the novel conveys the internal diversity of India’s Jewish community, comprised of Bagdadi Jews, Cochin Jews, and the Bene Israel Jews. For instance, Esther’s account of her famous aunt Dr. Jerusha, one of India’s first women doctors, illustrates how skin color and racism get intertwined under colonialism and divide the Jewish community. Although in love, Dr. Jerusha and her colleague Dr. Ezra, a Bagdadi Jew, could never get married. The Bagdadi Jews traditionally scorned the Bene Israel as inauthentic and darker skinned—and so Jerusha’s father David refuses to allow her to marry him.

The Dandekar men in Book of Esther are a motley crew: fascinating, intrepid, and at times, inflexible patriarchs who, across the generations, move from the farm in Alibaug to urban professional lives as elected representatives (David), doctors, and vets (Joshua, Samuel, and others). Section three “Joshua” revolves around an eponymous character modeled on David’s father Reuben. It beautifully captures how Joshua, like Reuben, starts out as a professional hunter who arranges hunts for the local royal families, but ends up a tireless conservationist. After his father David coaxes him into completing a British correspondence degree in veterinarian studies, Joshua becomes a self-taught zoologist and taxidermist who establishes Ahmedabad’s first zoo—the Hill Garden Zoo. For his path-breaking conservation work, Reuben David was awarded the Indian Government’s fourth highest honor the Padma Shri in 1975.The novel depicts seminal moments in Joshua’s life-when the then Prime Minister Nehru visits the zoo, and Joshua’s encounters with panthers, ostriches, and lion cubs that arrive there—effectively conveying the mutual affection, compassion, and respect that mark his relationships with the zoo’s denizens. Esther’s account of growing up with “Joshua and his menagerie,” her startling and at times humorous depiction of the deeply touching bonds between its human and non-human inhabitants, is one of the most unique, resonant, and strangely moving parts of the book.

The final section “Esther” is the most autobiographical; it also returns to the questions about marriage and intimacy raised earlier, as they appear in Esther’s tumultuous life. It is a frank and honest memoir of her experiences of sexual and domestic violence, custody battles, poverty, and loneliness. Even as friends, lovers, and husbands move in and out of her life from America and Paris, we see David becoming an artist and a writer as a single mother. There is the story of her rediscovery of her Jewish heritage, her son’s disability, her migration to Israel and Paris even as she watches young men leaving for the United States, and eventually Esther’s reinvention of identity and diasporic intimacy, as both Jewish and Indian.

Spanning the nineteenth and twenty-first centuries, with characters that travel across villages and countries, from Alibaug to Bombay, Ahmedabad, America, Paris, and Tel Aviv, Book of Esther paints a charming, vivid, and surprising picture of spirited Indian Jewish men and women who defy convention, and fashion provincial, cross-cultural intimacies. Like her other works Book of Rachel and The Walled Citythe novel is rooted in the flavor and color of the local particularity of the Jewish communities in the Konkan, and in Ahmedabad. Simultaneously, it poignantly depicts people shaped by the long, global experience of dispersal and diaspora, and its provincial beauty–one that resonates in uncanny ways with American writing on minority experience.

Kavita Daiya

Visiting NEH Chair in the Humanities, 2015-2016

Albright College

Associate Professor of English

George Washington University

Histories of Migration and Violence Digital Archive: www.1947Partition.org

Violent Belongings: Partition, Gender and National Culture in Postcolonial India(paperback)

Associate Editor, South Asian Review

Jews celebrate their New Year by blowing the Shofar or Ram’s horn in Synagogues all over the world, to welcome the New Year, leading towards the Day of Atonement or Yom Kippur. These are also days of self-examination, when prayers are said to seek forgiveness from God; for wrongs done during the year, which is followed by Succoth or the feast of tabernacles, observed by dwelling in tents at the Synagogue. It is symbolic of the forty years of wandering, before the Jews returned to Israel.

Jews celebrate their New Year by blowing the Shofar or Ram’s horn in Synagogues all over the world, to welcome the New Year, leading towards the Day of Atonement or Yom Kippur. These are also days of self-examination, when prayers are said to seek forgiveness from God; for wrongs done during the year, which is followed by Succoth or the feast of tabernacles, observed by dwelling in tents at the Synagogue. It is symbolic of the forty years of wandering, before the Jews returned to Israel.